I’m sure you all know the famous poem by W. H. Davies:

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare?—No time to stand beneath the boughs,

And stare as long as sheep and cows:No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass:No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night:No time to turn at Beauty's glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance:No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began?A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

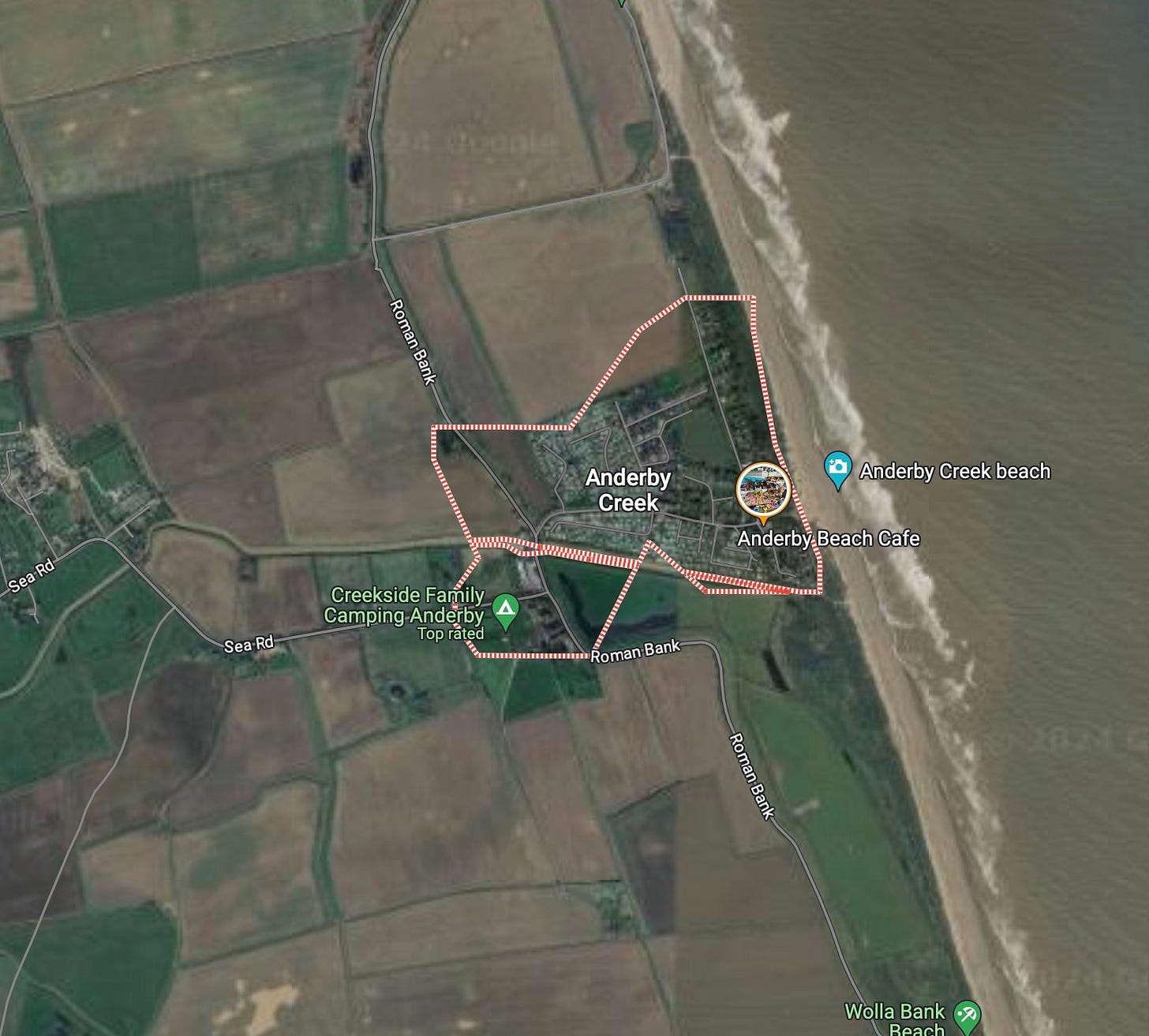

It just so happens that this weekend, I had the rare opportunity to do some standing and staring of my own, on a little-known beach in Lincolnshire called Anderby Creek.

This is a place hidden from most tourists. Although it is surrounded by campsites and caravan parks, it has none of the bright lights of nearby Mablethorpe, recently voted the second worst seaside resort in the UK.

I’m joking about the bright lights. Whatever unblown bulbs remain there are dimmed now. Mablethorpe doesn’t even have faded grandeur. It’s just faded, a paint-peeling facsimile of another rather grim seaside town that I remember from my youth: Canvey Island in Essex.

But what even Mablethorpe has that Canvey Island doesn’t, on the seaward side of the shove ha’penny arcades and the purveyors of deep fried fish, chips and doughnuts (all cooked in the same residue-ridden oil), is a beautiful, broad beach that stretches north and south as far as the eye can see.

Anderby Creek is a few miles to the south, at the eastern tip of the country reached by driving along sweeping lanes that wind through the beautiful Lincolnshire Wolds, and shares the same spectacular coast. When we visited, the tide was on the ebb and revealed acres of wave-washed sands, still bearing the imprint of the ripples that had now receded. And running down from the dunes at the head of the beach were countless rivulets of rushing water, mere inches deep but, in so many ways, microcosms of the mighty rivers that fill the seas around us.

And it was beside one of these tiny creeks that I stood, cameraphone in hand, transfixed by the games played by its tiny currents, the sparkling light and the sand beneath, the scene changing constantly as the force of the tiny torrent shifted little sandbanks, collapsed miniature cliffs and washed away momentary underwater obstructions.

I hope you can spare the less than five minutes needed to watch this short video and, as I did, feel rapt by these little scenes of wonder, like a glimpse into a tiny world which differs only in terms of scale from our own. It is a scene, of course, that is erased every time the tide comes back in, and is then replayed each time the waves recede, revealing a fresh canvas for these processes to play out. It’s all in the details.

Henry

Share this post